I rebuilt my personal site over the past few weeks after accidentally discovering Astro (it was the system Cerebro decided on when creating the Signal Over Noise site) What started as “maybe I should try Astro” turned into a complete migration from WordPress to a static site, with AI as a genuine collaborator throughout the process.

Why Leave WordPress?

I’d been on WordPress for years as both a writer and a developer. It worked, but several things were bothering me:

I was writing in Markdown anyway. Every post started as a markdown file in Drafts, Ulysses or (now) Obsidian. Then I’d copy it to WordPress, reformat it, fix the images, preview it three times, and finally hit publish. I’ve looked at plugins and other ways to reduce the friction between writing and publishing but they also require a level of technical maintenance that, while I can handle it, I would prefer not to have to.

I wanted to own my content as files. WordPress stores everything in a database. If I want to grep through my posts, or version control them, or process them with scripts, I’m fighting the system. Markdown files in a folder are simpler.

The attack surface. If website tools wore targets, WordPress’s would be the largest. Plugins need constant updating. Security patches need applying. I wanted something I could deploy and forget.

Speed. A static site is just HTML files. No database queries, no PHP execution, no caching plugins trying to make dynamic content feel static.

The Astro Decision (by Cerebro)

I looked at Hugo, Eleventy, Next.js, and Astro. I went with Astro for a few reasons:

Zero JavaScript by default. Astro ships HTML. If a page doesn’t need interactivity, it doesn’t ship JS. For a content site, this is exactly right.

Content collections. Astro has first-class support for markdown content with typed frontmatter. My blog posts live in src/content/blog/ as markdown files, and Astro validates the frontmatter at build time. No more “oops, I forgot the date field” surprises in production.

Islands architecture. When I do need interactivity, I can add it surgically. The rest of the page stays static.

It’s just components. Coming from React/Vue, Astro’s .astro component syntax felt familiar. No new templating language to learn.

Importing WordPress Content

This was the tedious part.

WordPress has an XML export, but what you really want is markdown files with proper frontmatter. I used a combination of:

- WordPress export to get the content

- A conversion script to turn HTML into markdown

- Manual cleanup for the posts that didn’t convert cleanly (there were many)

- Organizing into Astro’s content collection structure:

src/content/blog/YYYY/MM/DD/slug/index.md

The images were their own adventure. WordPress stores them in wp-content/uploads/YYYY/MM/, and post content references them with absolute URLs. I had to:

- Download all the images

- Organize them into sensible folders

- Update all the references in the markdown files

Cerebro handled the bulk transformations — regex patterns, folder structure, edge cases. An afternoon instead of days.

Setting Up 301 Redirects

URL structure changed. Old WordPress URLs looked like /2024/11/post-title/. New Astro URLs are /blog/post-slug/.

Every old URL needs to redirect to its new location, or I lose years of SEO equity and break every external link to my content.

I generated a redirect map by:

- Extracting all URLs from the old WordPress sitemap

- Mapping each to its new Astro equivalent

- Generating redirect rules for my hosting provider

Cerebro did most of the mapping automatically, flagging ambiguous cases for me to review. The result is a redirect config that handles hundreds of URL patterns.

Defining the Aesthetic

I spent more time on visual identity than I expected.

The web is drowning in the same aesthetic: Inter font, purple-to-blue gradients, uniform rounded corners, generic stock photos. I wanted something that felt distinctly mine.

I landed on claymorphic — soft 3D illustrations with a clay/polymer look. Warm peach and cream backgrounds. Isometric diorama compositions. The kind of imagery that looks like a Blender render of a cozy miniature world.

This became the template for all hero images:

- Isometric diorama perspective

- Warm cream/peach background

- Soft matte clay textures

- Rounded, pillow-like edges on objects

- Gentle ambient lighting with soft shadows

- Teal and burnt orange accent colors

I documented this in a style guide and built it into my /art skill, so every time I generate a hero image, it follows the same aesthetic automatically. Consistency without having to remember the details.

The Web Architect Agent

As I was building the site, I realized I kept making the same decisions over and over: which CSS approach to use, how to structure components, what accessibility checks to run. So I captured all of that into a specialized Claude Code agent.

The web-architect agent has opinions about:

Typography. Never use Inter alone. Distinctive display fonts paired with readable body fonts.

Accessibility. WCAG 2.1 AA compliance is non-negotiable. Skip links, focus states, color contrast, heading hierarchy — the agent checks all of it.

Performance. Lighthouse 90+ or justify why not. Image optimization is mandatory.

Animations. CSS for micro-interactions, Anime.js for scroll-triggered reveals, Three.js only when it adds genuine value.

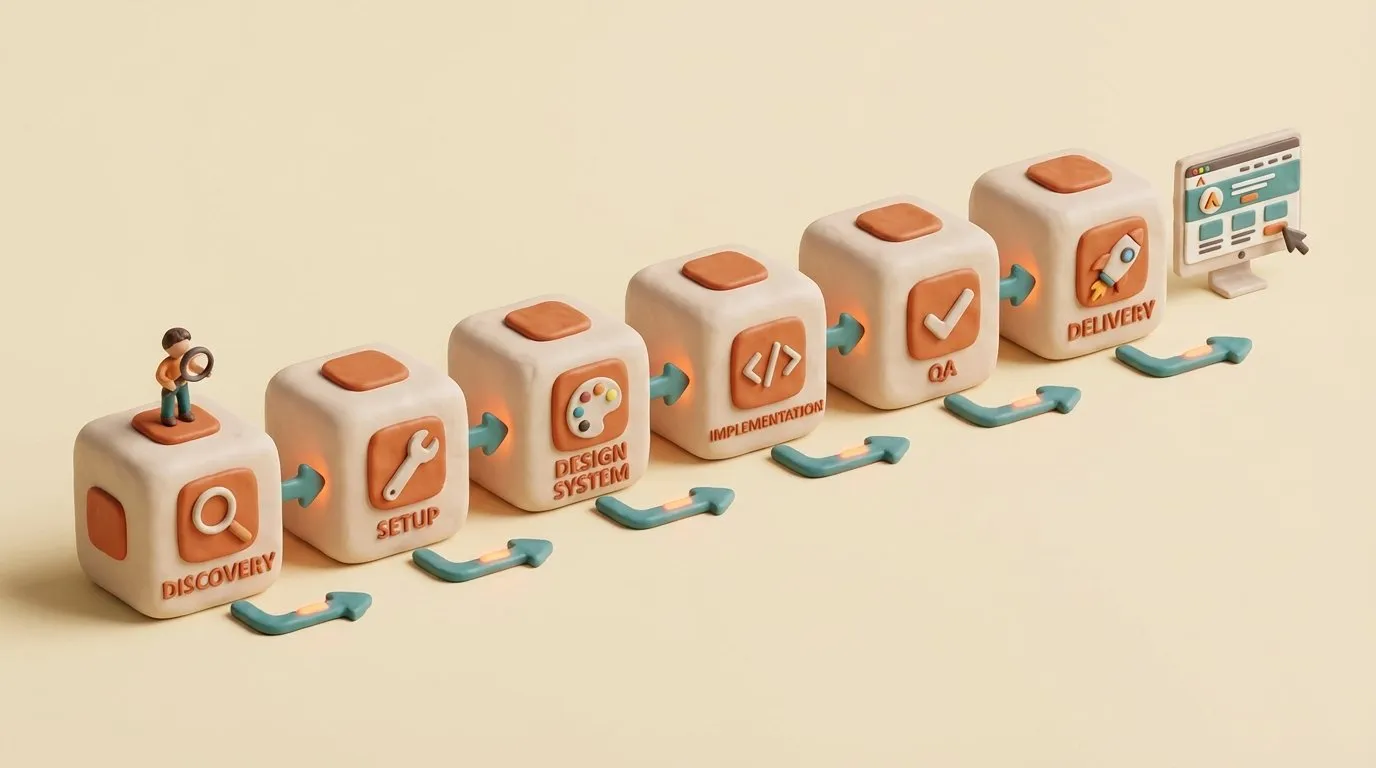

The agent also includes a complete workflow: discovery → setup → design system → implementation → QA → delivery.

When I start a new site project now, I don’t start from scratch. I start with the web-architect agent and its accumulated decisions.

Image Optimization

After migrating all my content, my public/images/ folder was 245MB. Some images were over 5MB each. AI-generated images are often huge, and I’d been dumping them in without optimization. While I’m a huge fan of Squoosh.app, I didn’t want to drag and drop the images manually when I have a computer that’s learning how to do stuff for me sitting right here (/gestures around).

Two tools fixed it:

# PNG optimization (Squoosh-quality)

find public/images -name "*.png" -size +500k \

-exec pngquant --quality=65-80 --force --output {} {} \;

# JPEG optimization

find public/images \( -name "*.jpg" -o -name "*.jpeg" \) -size +500k \

-exec jpegoptim --max=85 --strip-all {} \;245MB → 163MB. A 33% reduction with no visible quality loss. Some individual images dropped by 90%.

I added image optimization to the web-architect agent’s QA phase so I won’t forget again. Every site I build now gets optimized images before deployment.

What I Learned

Migration is the hard part. Setting up Astro took an afternoon. Migrating years of WordPress content took weeks, including checking 301 redirects. If you’re planning a similar move, budget your time accordingly.

AI handles the tedious parts. Regex patterns, redirect mapping, frontmatter cleanup — Cerebro did most of this while I focused on decisions.

Codify decisions. Font choice, component structure, image quality settings — every decision went into the web-architect agent. Now I delegate instead of remembering.

A defined aesthetic saves time. Once I documented the claymorphic style, every hero image decision for the site became automatic. Templates always beat starting from scratch every time.

Static is simpler. No database to back up. No plugins to update. No security patches to apply. Just HTML files on a server. The site loads fast, deploys with an FTP push, and I don’t worry about it.

The Current Stack

For the curious:

- Framework: Astro 5.x with content collections

- Styling: Custom CSS with design tokens (no Tailwind, no framework)

- Images: AI-generated with Flux/Nano Banana Pro, optimized with pngquant/jpegoptim

- Source of truth: Git repository + Obsidian vault

- Development: Cerebro (Claude Code + Obsidian) with custom web-architect agent

What’s Next

The site is live and I’m actually publishing again. The friction that stopped me before is gone.

Still on the list:

- Better search functionality

- Reading time estimates

- Series/collections for related posts

- Maybe a dark mode that doesn’t suck

But for now, I’m enjoying the simplicity of writing in markdown and deploying with a git push. Which was the whole point.